|

The following text and pictures

are taken from an article

published in a British magazine

entitled JOHN BULL dated

Week Ending February 4th 1956

It covers early development of

Bluebird K7, and Donald's first

Water Speed Record of 202mph

on Ullswater on 23rd July 1955

|

SPEED IN MY BLOOD

We go begging for £10,000

Our aim was to bring a world record back to Britain

We had to find more money - but people weren't eager to help

By Donald Campbell

|

The three-foot speedboat-a scale model of what was to be the new Bluebird - was powered with a hydrogen - peroxide rocket. This was the nearest we could get to the jet engine of the real thing. On a small lake near Osborne, in the Isle of Wight, we laid out a miniature trials course: accurately measured, it even had sighting-posts on the lake shore. Here we carried out the preliminary tests for the project on which I had set my heart-to win back for Britain the world's water speed record which my father had once held.

We had to treat the rocket fuel with great respect-if even an eggcupful was spilt on the grass a wisp of smoke would curl up, to be followed half a minute later by an intense fire. When one of our team trod in a minute pool of the stuff his shoe suddenly burst into flame, and his sprint to the lake for a quick paddle must have been a near record.

The little craft incorporated all the know-how I had gained from my previous record attempts and was designed by the Norris brothers, Kenneth and Lewis, brilliant engineers who had their own firm at Burgess Hill, in Sussex. It was radio-controlled and ran well; we learned a lot about its performance- facts that would be invaluable when we built the full-scale Bluebird. The only setback was when the radio unit developed a fault and the craft veered off course, hitting the bank at fifty miles an hour and tearing off one of its floats.

The model finally smashed itself to smithereens at dawn one morning when it ran ashore at eighty miles an hour. The crash and the explosion of gas from the rocket so startled an elderly carthorse in the next field that he interrupted his breakfast with a burst of speed that would have won him the Derby.

It was spring, 1953, not quite a year after the American, Stanley Sayers-who had already captured the world water speed record set up by my father-had increased his own record to nearly 180 miles an hour.

Leo Villa, my father's old chief mechanic, and I accepted the challenge and planned to build an entirely new Bluebird, a hydroplane speedboat, to get that record back for Britain. It was not easy. I sank every penny I possessed into the project and tried to get backing from the big aircraft and marine engineering firms. Nearly all of them said that they were unable to help, but we did manage to get our test model built and, more important still, we obtained a jet engine to power Bluebird.

It was a worrying period, especially for Dorothy, my wife. We had met for the first time at Coniston in 1950. Dorothy McKegg was one of four New Zealand girls on a holiday motoring tour of the Lake District. It was before the old Bluebird crashed disastrously, and they came to see her. Dorothy and I met again, accidentally, at Southampton and we were married at Reigate in March, 1952.

For Dorothy, marriage to a husband and a boat as well has not been all fun. My long hours of work and the periods when I have been away from home for days-sometimes weeks- often destroyed any chance of a social life; but Dorothy has always been cheerful, tolerant and understanding. And when life has been more than usually difficult-during the new Bluebird project, for instance-she has been an invaluable help to me. There have been so many periods when her patience has been sorely tried by my worries and moods, yet she has rarely complained.

After the Osborne trials, the next task was to construct another model, this time for wind- tunnel tests. We carried these out at the Imperial College of Science and Technology at South Kensington. There, with the help of Tom Fink and his post-graduate students, we amassed a pile of figures to guide us in shaping Bluebird's hull in the form that would give maximum speed.

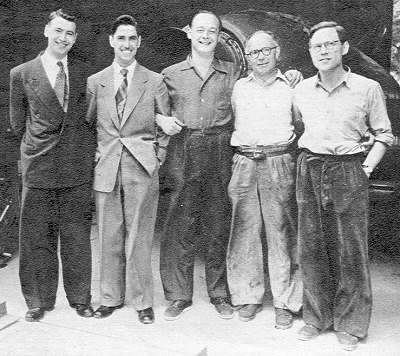

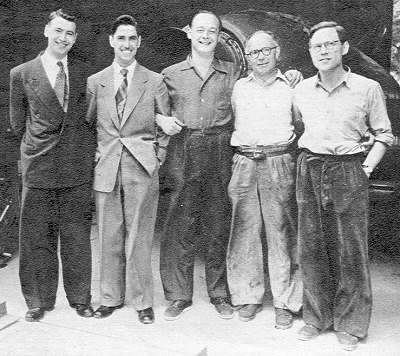

Some of the men who planned the jet Bluebird: Lewis and Kenneth Norris (designers), Donald Campbell, Leo Villa (the chief engineer) and Tom Fink of the Imperial College of Science.

|

Now that we were satisfied with the design, we had to start building-and that meant finance.

I estimated that the total cost would be about £25,000, and when I had put in all that remained of my own capital we still had to find £10,000.

I appealed to many people for help, and most of them refused. Yet we were not entirely alone. One or two big firms and a lot of little ones supported us: we were offered £100 here, £250 there. Bill Coley, an old family friend who is in the scrap metal business, gave me a cheque for £2,500. It was all a gamble, but we had confidence and we went ahead.

Bluebird was to be an all-metal boat. Throughout 1954 she took shape-first frame, then hull. The jet engine was delivered to my home, Abbotts, near Dorking, Surrey, where Leo Villa and I taught ourselves how to handle it.

Bluebird was to be linked to the shore by radio telephone, and I decided to equip the cockpit with oxygen in case of accidental submersion. I began to think of a breathing apparatus combined with a microphone, and my thoughts turned to Neville Duke, chief test pilot of Hawker Aircraft, whom I had met on a number of occasions.

I rang up Neville, and he invited me over to Dunsfold Airfield. I explained what I had in mind. "Perhaps a high-altitude pressure mask might do the trick," he said, and showed me the type used in the Hawker Hunter.

It looks just the job,' I remarked after he had explained how it worked. "Where can I get one?" "Have mine," said Neville. "You're very welcome to it. And you'd better have the crash helmet we always wear as well."

He showed me the Hunter, made valuable comments on cockpit layout, and I left Dunsfold with his mask and helmet.

Soon after this I met Captain Bill Shelford, who had recently given up command of the R.N. Diving School at Portsmouth. He devised the idea of my using Neville's mask with a sort of aqualung developed for underwater swimming.

"What about trying it out in the experimental tank at Tolworth ?" he suggested.

It seemed a reasonable idea to me as I drove over to Tolworth, not far from Abbotts; but I was inclined to have second thoughts for a few moments once I had put on the mask, which was attached to a compressed-air supply outside the tank. There is something rather cold-blooded in descending a ladder into deepish water; perhaps I felt a touch of claustrophobia. 1 hesitated on the top rung, wishing I had stayed at home and that there were not so many people watching-so that I could change my mind.

There was no way out of it, so down and down I stepped, feeling strange but finding to my astonishment that I could breathe easily. I stayed on the bottom of the tank for a few minutes and then climbed out feeling quite pleased and not a little relieved. After that it was no trouble-in fact it was rather fun.

|

Escape kit testes at Tolworth. "I hesitated on the top rung," says Donald Campbell.

|

Things were now well enough advanced for us to think about full-scale trials and plan our record attempt. We decided to base ourselves on Ullswater, in Westmorland. Here a local steamer company provided a pier, near the little town of Glenridding, where we could erect our boathouse and special slipway.

I got together a team of engineers to work with Leo Villa to install the jet engine in the now-completed hull and fit the controls. Back at Abbotts, I carried on with the administrative side, dealing with hundreds of details, nearly twenty-five letters a day and innumerable telephone calls.

September passed and October, with the team hard at work, before we could fix the date for completing Bluebird and holding the official ceremony when she would be shown to the public for the first time. Finally we decided on November 26 and sent nearly seven hundred invitations to our friends, to industry and to many we thought would be interested. And from that moment onwards we were often to wonder whether the boat would really be ready, even with the long hours worked by Leo and the team.

She was, in fact, far from complete on the day of the ceremony, although she appeared ready to go out on Ullswater.

By now the project had eaten up about £18,000, including all my limited capital. Expenses had been enormous, averaging about £250 a week for wages, travelling, printing, stationery, lighting, heating, telephones-all the usual items of any business, but, unlike other businesses, we had nothing coming in.

I had travelled well over 100,000 miles for fund-raising talks and meetings; my appeals were answered by a few friends. But there was little other assistance offered.

I was faced with the prospect of borrowing money to carry on. Rather than become involved in that way, I mortgaged Abbotts in what was really quite a desperate attempt to keep going. Now every penny I had was invested or tied up in the new Bluebird.

It was a grim period. Yet there was light as well as shade. At the end of October. Bill Coley's father telephoned.

"Come over for a drink, Donald," he said. "I'm going to celebrate my seventy-sixth birthday." "Many happy returns, sir," I replied. "I'm on my way."

There I found Dorothy smiling at me, and the Coley family, my sister, Jean, and her husband, Leo, the Norrises, all with their wives-and many others. Bob called for silence after I had received an uproarious welcome. He wanted, he said, to make a speech. He proceeded to wish me and everyone associated with me good luck with the new boat and to hope we would win the world water speed record for Britain.

"And we want you to accept this to go on your dashboard," he added. "This" was a St. Christopher medallion in white and blue enamel on silver, unclasping to reveal the names of everybody at the party. I was deeply touched and thanked them all as well as I could.

It was Leo who had the idea of the medallion, for he knows I always wear a small gold St. Christopher charm round my neck, given me for luck by Father. And he also suggested, with typical thoughtfulness, that Bob Coley should present it to me on his seventy-sixth birthday.

The medallion is now screwed on the instrument panel of Bluebird's cockpit, a pleasant reminder of my closest friends. It was a happy interlude during a period of complications.

There was further delay with completion of the slipway at Glenridding. and trouble with the boat's steering-control gear. It was not until ten weeks after her public appearance that Bluebird was ready to be launched into Ullswater.

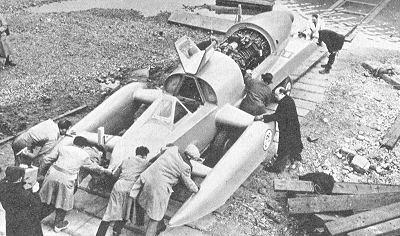

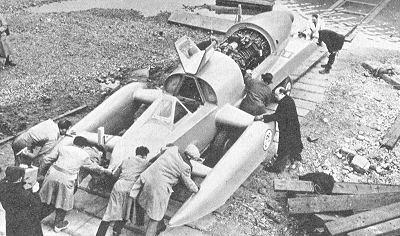

Friday, February 11, 1955, dawned clear and fine. We decided that the naming ceremony should be performed by Dorothy and that I should make a trial run. Watched by Leo and the team, Brian, Jean, the Norris brothers and a number of friends. Dorothy swung a bottle of champagne to strike an iron bar above the boat.

She repeated the words I had spoken in 1939: "I name this boat Bluebird. May God bless her, and her pilot, and all who work with her."

Dorothy Campbell names the jet Bluebird. Beside her are Campbell's sister (Jean Hulme), Cambell and Leo Villa (in cap).

|

I stepped into the cockpit, the cradle was lowered down the rails and Bluebird gently drifted free. We towed her out into the lake and I prepared for my first run in a hydroplane since the old Bluebird crashed on Coniston.

We had waited nearly three and a half years for this moment.

February 1955 - the jet boat Bluebird takes to the water for the first time.

|

I pressed the button and heard the starter come in. The revolution counter began to climb-400, 500. 600, 700. The jet started quickly and was soon idling sweetly. I felt a thrill of delight. Bluebird was under power for the first time, moving forward gently at five miles an hour. I turned the wheel to port. She answered immediately and swung round easily; over to starboard and again the quick response. There was no doubt about her low-speed manoeuvrability. She turned beautifully.

It was too soon to start congratulating ourselves-trouble lay ahead. First we could not get Bluebird correctly trimmed to plane on the water at speed. In bitter, freezing weather, we carried out the necessary modifications.

Then, when she planed at speed, water sprayed into the jet engine and stopped it; this was to be our biggest problem, but for the moment we got over it and I started serious trials-and they were not without their hazardous moments.

As I came in from one run the air speed indicator failed. I passed the pier at what I estimated to be about eighty miles an hour and turned into the small bay, expecting the speed to fall away. Suddenly I realized that Bluebird was travelling much too fast and that she was not going to stop. Normally I could have pulled her up short by releasing the parachute arrester. But this was not fitted.

There was only one thing to do-yaw. I turned Bluebird towards the bank on her starboard side and then swung her over sharply to face the bank on the port side to slow her down. Still she was moving freely-and now there was no further room to turn.

Bluebird rushed towards the bank-and what a rocky, steep bank it seemed! Just as I was bracing myself for a collision her nose dropped and she stopped six feet clear of a very fat boulder.

There were many white faces when I went ashore at the pier. One of them was Leo's. He came up to me looking pale and angry.

"Look here!" he said sharply. "You're not playing the game. You're just playing the fool going on like this."

My nerves were not as calm as they might have been, and I turned on him with one of Father's favourite expressions: "Who the hell do you think you're talking to? Instead of standing there making damned stupid remarks get that indicator put right."

We glared at one another and burst out laughing.

To give me an idea of what Bluebird looked like in action. Leo took her out himself, while I sat in a speedboat in the middle of the lake with a pair of field glasses.

Leo took Bluebird away skilfully, quickly reached the planing condition at about forty miles an hour. When he slowed down, the usual shower of water from the spars and floats covered the cockpit and he got a ducking similar to those I had experienced, for the cover was a poor fit and water streamed in.

It was now that I became really frightened. I thought Bluebird was making straight for a headland and was about to crash on the shore. Sud denly I realized that water must have covered Leo's glasses and temporarily blinded him, and I imagined that he had lost control of the boat.

I called him up on the R.T.

Everything all right, Leo? If so, give me a wave."

Looking through the field glasses I saw him wave. I felt much better.

He brought Bluebird alongside the pier and stopped at the right spot, although he was troubled still by his glasses and the glare of sunshine on the screen.

"Well, Leo. Enjoy it?" I asked when he was ashore.

"Fine, Donald! Wonderful! I'm afraid I didn't get any instrument readings as I intended. It was all very bewildering."

"Now you know that it's not quite as easy as it sounds,' I said to pull his leg. "By golly, you gave me a fright. I thought you were going straight into the bank."

"And now you know what we go through when we're watching you," Leo answered. "I got covered in water and couldn't see a thing through my glasses. But I was a long way from land. It was a wonderful feeling when she began to plane."

Bluebird's performances had been well reported and the news that she could reach 150 miles an hour in a quarter of a mile had been cabled to the United States, where the Navy Department in Washington put a request through via the Admiralty for information about Bluebird. It gave me considerable satisfaction to supply it.

Then, during the debate on the Naval Estimates in the House of Commons, one of the members asked the Civil Lord what interest the Admiralty was taking in Bluebird and whether he knew there had been an inquiry from the United States.

This set Fleet Street telephoning my hotel. Our tails were well up that night.

In the next testing phase we found that the problem of spray getting to the engine became acute at high speeds. There was only one thing to do-modify the design of the hull. There followed days and nights of work, frustration and worry.

I had arranged to rent two houses near Glenridding for Dorothy and l myself and the team. In spite of our troubles we were a happy, cheerful party with everyone pulling his full weight.

Dorothy and my mother, who came over from Windermere, were bricks. At the boathouse they kept us going with tea during the morning and afternoon and also brought us our lunch. We could keep working until nine or ten at night before returning for the evening meal, and sometimes we did not pack up until after eleven.

Dorothy and I were able to see much more of one another than for some months past, and we enjoyed life in our stone house set in a wood on a hill overlooking the main leg of the lake.

Our patience was often tried by various complications. A railway strike occurred when we needed material urgently for the modifications.

There were also our finances, over which I brooded continuously. Nothing, absolutely nothing, was coming into our kitty, which had a voracious appetite. It was true that people were queueing to see Bluebird and paying one shilling each, but this money was collected by the steamer company, in return for providing us with the boathouse and the slipway. which was fair enough.

Just when I was desperate for money. Bill Coley came once again to the rescue. He gave me another cheque for a £1,000.

Call it a loan, Donald." he said. "But if it doesn't work out that way, well I shan't worry."

You can imagine my feelings. Another old friend sent me a cheque and I raised a small amount from another source. We were able to keep clear of the financial rocks, but they were pretty near and always looked most forbidding.

Summer came to the Lake District; the hills, so harsh and brown before they were covered by snow in winter, were mantled in soft greens; the biting cold that had so regularly gnawed at us in the boathouse gave way to an almost drowsy heat.

Dorothy swam daily, and when, with Mother, she began to patrol the course searching for driftwood, her chief delight was to be towed behind the launch. A considerable amount of driftwood was collected, including one entire tree trunk; it drifted three miles during the night after being spotted at sundown. Maxie, my "labradoodle" dog, lolled around the house panting, and there was always a warm welcome from him at night.

Gradually Bluebird took on her new look. Her nose became more snubbed and less pointed, her front spars were raised and joined to the floats by smooth elbows, spray baffles were built on either side of the cockpit, a new Perspex canopy was fitted.

Finally the day came when Leo said: Well, Don, you can take her out tomorrow, boy." And so on July 9 Bluebird went down the slipway on her cradle and into the lake for the first time since March.

All went well until I had worked her up to nearly 140 miles an hour. Then I had a positive test as a pilot. Heading towards the turn into the main leg of the lake I saw one of the lake's passenger steamers rounding the headland. There was a gap of about forty yards between it and the island at the end of the Glenridding leg. I steered for the gap, passed the steamer and the next moment hit her wash. Bluebird reared like a bucking horse, throwing me about violently; but the harness held me in position and prevented my going out through the Perspex canopy; we came out of it all right.

More trials, more minor modifications; then on July 13 I informed the Marine Motoring Association that we intended to make an attempt on the world water speed record. From that moment onward we were to have no peace. Bluebird seemed to become a gigantic machine in which we were merely cogs.

As soon as the news was published, a spate of reporters and cameramen began to flood into our small village, all wanting to know when we were going to make our record attempt and seeking general information about Bluebird.

In the middle of it, my back, which had been uncomfortable ever since a schoolboy rugger injury, began to trouble me seriously for the first time in years and I had to arrange for a masseur to give me treatment.

More days of expectant crowds, unsuitable weather conditions and minor hitches followed. On July 23 I was due to take Bluebird out to test some adjustments we had made to her rudder.

I had told nobody, but in my own mind I knew that if the water conditions were right when I brought Bluebird up to the measured course this morning, my foot was going down on that accelerator. The general strain was beginning to tell on me and I wanted to get the whole thing over and done with.

I was depressed and a little tetchy as I walked down the concrete slipway from the boathouse, my back was giving me hell and I was thinking how wonderful it would be to go hack to bed and lie down again.

Two of the team were standing beside Bluebird in their blue overalls. All ready, sir," said one of them.

"Thanks," I answered and threw away my cigarette and stepped on to the starboard float with my rubber- soled shoes, leaned over and gripped the top of the Perspex hood, stepped on to the soft, blue G seat and slid gently down to sit with my legs on either side of the steering wheel. It is a pretty tight fit in the cockpit, just enough room for me. With my mind busy I forgot the pain in my back.

Let's see now. . . . On with Neville's helmet, ears inside the rubber rings, fasten the chin strap, slip the pressure breathing mask with its microphone across my face. See that the valve is on atmospheric breathing. Plug in the radio lead, switch on. Check.

"Skipper calling Zebra. Skipper calling Zebra. Over."

"Zebra replying. O.K. Skipper. Able reports all O.K. and the water perfect."

"Skipper to Zebra. Thank you. Stand by. Over."

It's a pretty small world in this silvery cockpit. The black, shiny plastic wheel is handy in front of me and well forward, the dashboard is black but relieved by four dials. If I glance left and right I can just see the blue tips of the floats, if I look ahead slightly down I can see the snub nose of the cockpit. Ahead-the lake and the shore.

Skipper to Zebra. All set and starting up. Over."

O.K. Skipper."

I give the thumbs-up signal and press the starter button. There is a gentle purr, growing to a whine.

The engine is idling nicely and already there is plenty of thrust coming from the end of the jet pipe. Bluebird is straining on her mooring ropes wanting to be away. Suddenly she surges forward. We're off.

Moving slowly out of the trap. Clear of the pier. Helm hard over to port as we're facing a small, rocky island about a hundred yards away. Steer a course between the rock and the point of land on the port side. Now we're down, heading nicely on the track. Set a course to take us diagonally between the next two islands and down to the end of the main leg of the lake, which is the start of the course.

Now throttle down. Up come the revs. Nose up, not much, but noticeably. Lot of water coming over and some spray on the screen. Now there's a terrific rushing of air as the thrust really comes on. Stern up. Now she's planing. Hold her down, don't want to go too fast-fifty, sixty, seventy miles an hour. The second island is coming up fast. Start to ease her back.

Now we hit the measured course. Going very fast indeed-fairly rocketing into space. Now pay attention. Keep on track. Must keep into the middle. Wind comes down and catches the boat. Sliding away slightly. Bring her back, not too fast. Gently, gently. Back again, back again. Not too much or you'll over-correct.

We're in the middle. Have a look at the air-speed indicator. My god-fathers-the needle's right off the clockl

What is it? 205? 210? I don't know. Ease back slightly, slightly, slightly. Keep her on two hundred.

Leo, Leo. We're doing fine. Two hundred coming up. We've got it."

Flash out of the kilometre. Start to drop her back.

Coming in to refuel now. Slow down-cut the power-slide towards the base. Someone catches the starboard float; pushes her gently round. Right. Undo my harness. Now watch your back, boy. Ouch! Stabbing pain as I move. Canopy back. Stabbing pain as I reach up too far to lower it. Crawl out of the cockpit like an old man.

Now they're refuelling her. I can hardly move, my back is so stiff. I have a drink of orange squash and smoke a cigarette.

Back into the cockpit. Repeat the drill-get her planing. The stern's up and she starts to rocket away on course again.

Keep her on track, boy. She yaws. We're facing the shore. Bring her back, not too hard, not too hard, gently. Watch that island. Watch that headland. Bit close, but she seems to be going straight. Hold it steady. Here we are now, bang in the middle. Now we're coming towards the end.

Remember you haven't got much water. Lift your foot just before you clear the kilometre, you've got plenty of speed in hand. Past the buoy. Flash down towards the end of the lake. Careful now, you can see the buoy-line on the island.

It's over. Bluebird is taken in tow by the team and then Leo Villa, my chief mechanic and the man without whom none of it would have been possible, comes aboard. We sit together beside the cockpit, on either side of the air intakes.

"Fine show, Don," he says. "I can't tell you the speed-but you've got a new record

Leo gave me a big hug and I noticed there were tears in his eyes. Then my own eyes were a bit damp, too. It was a wonderful moment, the finest of all. "Thank God, Leo!" I said. "We've been struggling for it for six years."

We sat there, the two of us on Bluebird, while they towed us in, too full of emotion to talk any more.

Then the timekeepers were with us at the pier. They looked pleased and purposeful: "Congratulations, Don. Your average is 202.32 miles an hour..." I realized that I was 24 m.p.h. ahead of the record.

I felt a little dazed as they all grinned and gripped my hands. I called over Betty Coley, Bill's wife, and one or two close friends and told them quietly. Someone suggested that it was time to go up to the hotel. But I was not going to leave the catwalk until dear old Bill Coley and his son Christopher were back from the course.

When his launch was about a hundred yards away we could see Bill in his grey sweater. We gave him the double thumbs up and he jumped up and down with delight. Soon he was beside me and I whispered the figures. He grabbed me and thumped me and we both nearly fell into the lake, but saved ourselves by grabbing a rope.

|

Bill Coley (left) with Campbell immediately after the record run on Ullswater. Coley gave £2,500 towards the jet Bluebird.

|

And as the car jogged back to the hotel, past small knots of people, I thought of my father. It was just over six years since I had determined to improve his record to prevent it going to the United States; long years of bitter disappointment, frustration and hard work. Somehow at that moment it was difficult to realize that we had brought back the record to Britain. I felt almost like pinching myself to make certain I was awake and that this was no dream.

"We made it!" Campbell's mother smiles happily as her son embraces his wife and Leo Villa after the record run on Ullswater.

|

Father would have been pleased with our new record. But he wouldn't have been satisfied. Nor was I. We had designed Bluebird to do 250 miles an hour and none of us knew how close we could get to that target-or how dangerous it would be. Now I was going to America to find out.

(Four months later, on 16th November 1955, Donald set another new record of 216.20mph on Lake Mead)

Top